“Deep down”, writes Clarice Lispector in her short story Love (1960), “Ana had a constant need to feel the firm roots of things. And, bewilderingly, that is what a home had given her. Through winding paths, she had fallen into a woman’s fate, surprisingly fitting in as if she had invented it herself.”⁽¹⁾ Ana is a married woman, apparently happy with her daily life, satisfied with her domestic chores, despite the restlessness at “a certain time in the afternoon” where “the trees she had planted laughed at her.”⁽²⁾ Yet, one day, while riding the streetcar, the sight of a blind man chewing gum and then the luxurious nature of the plants and animals in the Botanical Gardens deeply disturb the solidity of Ana’s rooting, generating a “crisis” which combines pleasure and suffering - a love for the world and a desire for life which simultaneously attract and repel her. Back in her house, upon meeting her family once again, Ana, for a moment, feels like a foreigner in her own refuge, her home. How can one forget about this shattering love and return to the solidity of “before”?

The destabilising tension between rooting and estrangement, between the tranquillity of belonging somewhere and the restlessness of feeling foreign, so apparent in Lispector’s story, is also present, in slightly different ways, throughout the oral and visual narratives of the women who participated in the project Still here, sometimes there (2021), by artist Johanna Steindorf. In 2011 Steindorf invited 38 migrant women from several nationalities residing in multiple countries to take part in an audio walk entitled Still here, sometimes there. With the intent to take on a critical investigation of feminine migration and its relationships to the production of space in everyday life, the project invited participants, who were also listeners, to photograph a series of objects, situations and places at home and around their neighbourhoods. Ten years later, and after the experience of pandemic lockdowns, the artist reconnected with those women asking them to repeat the audio walk from 2011 and take part in an interview in an attempt to investigate how time, when intervening in the triangulation between migration, production of space and the affective and relational construction of subjectivity, can generate unprecedented transformations⁽³⁾.

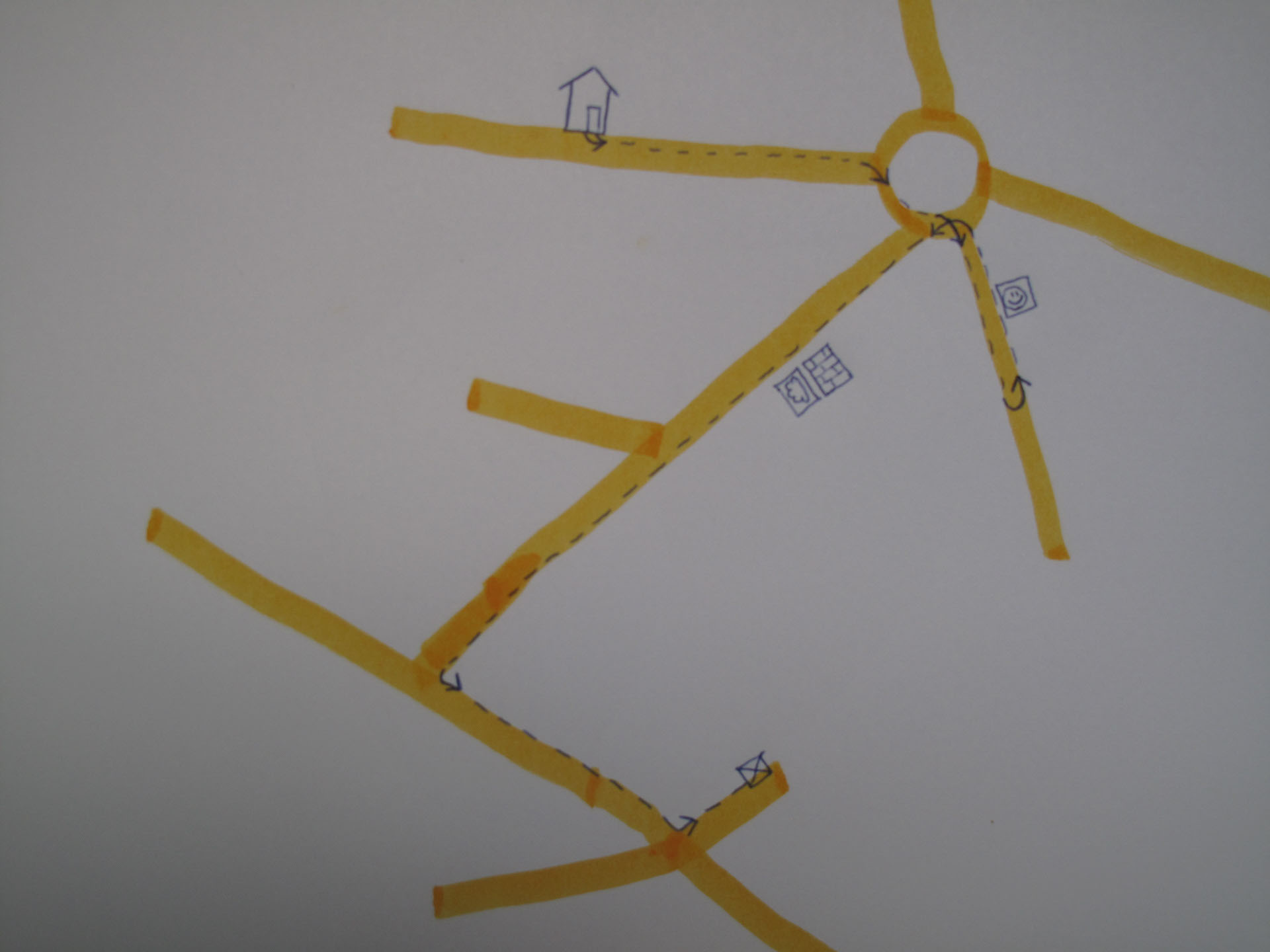

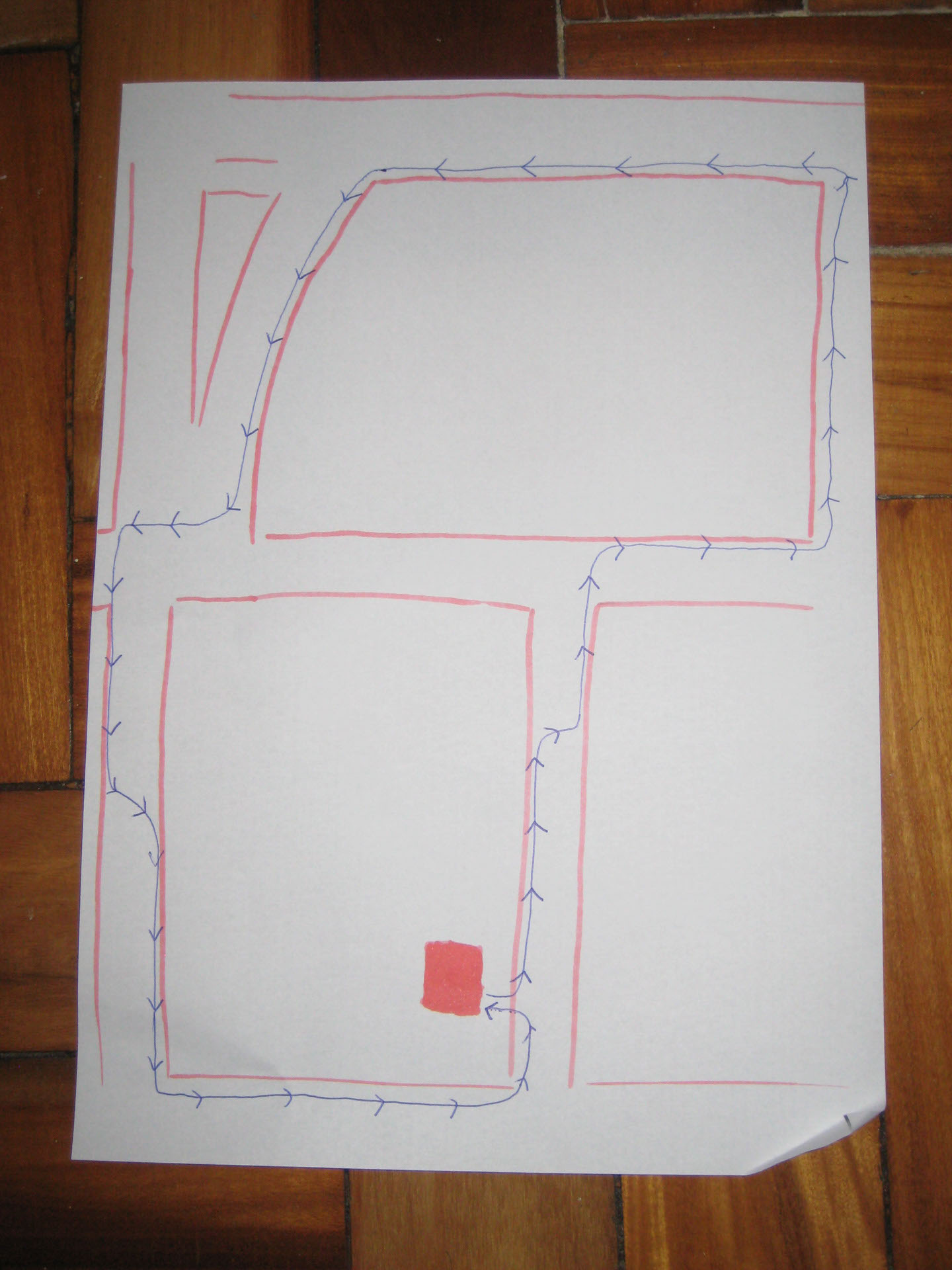

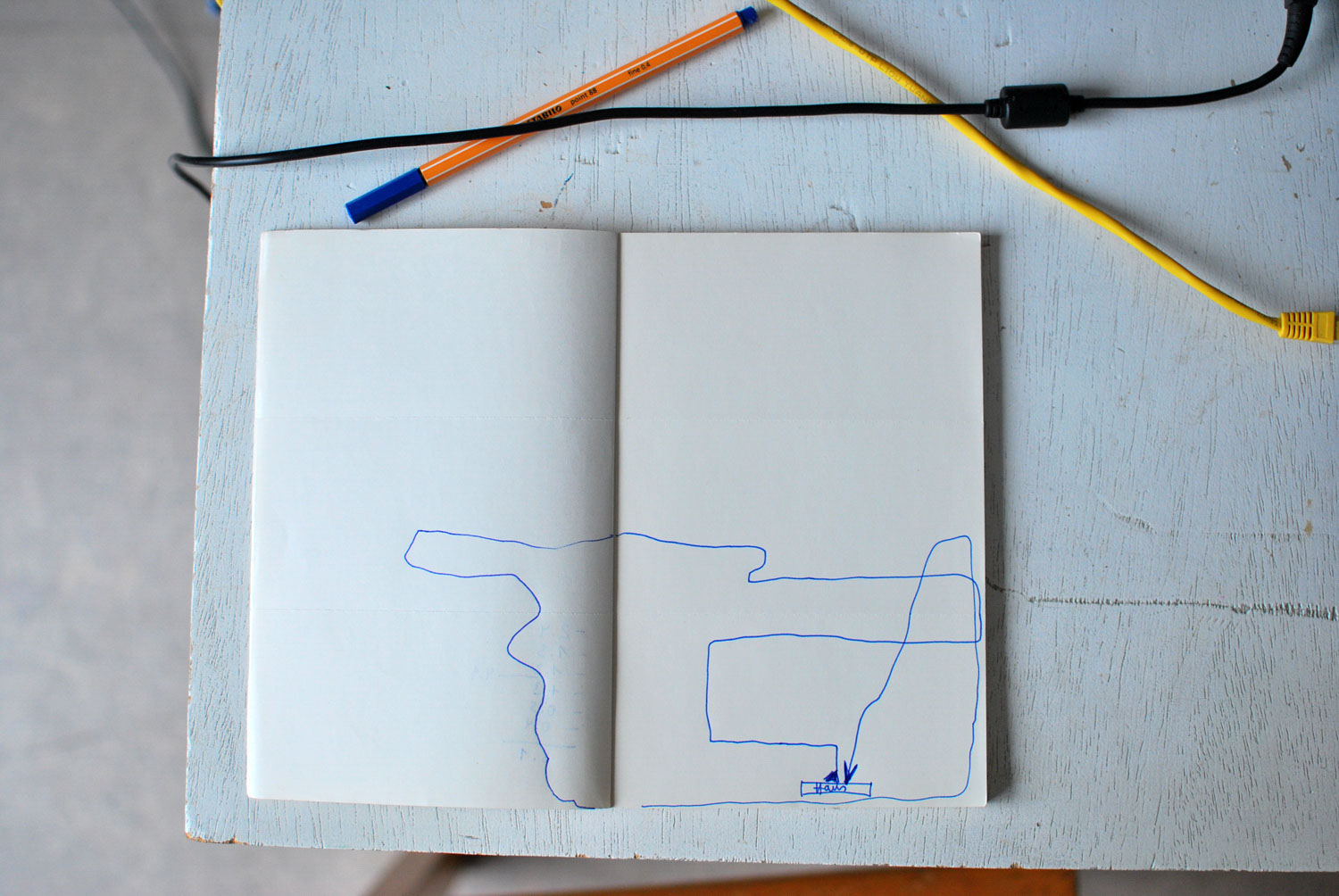

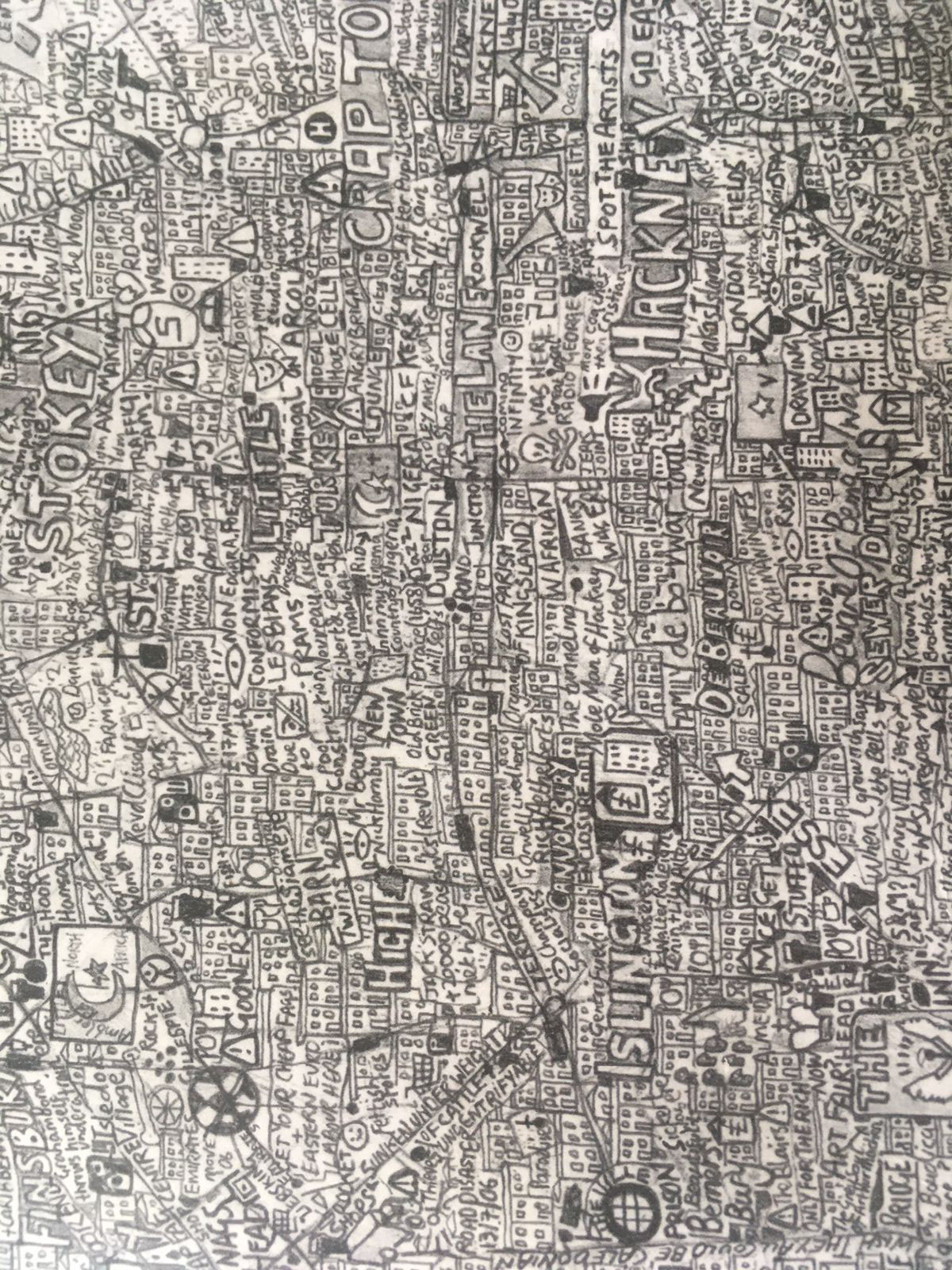

Still here, sometimes there (2021) proposes, then, a singularly intimate itinerary among the roughness and frictions, the spatial and temporal continuities and discontinuities - both real and imaginary - which run through the narratives constructed by participants. In this context, the audio walk, created in 2011 and reactivated ten years later, becomes the material and conceptual thread joining together both moments in which the artist’s project unfolds. This sound and performative art piece can be thought of as a device creating an immaterial connection space. In it, Steindorf directly addresses the listener / actor - “you” - proposing, through clear instructions, that they leave their house, walk around their neighbourhood for a while and then return home, and also directing where and how to photograph specific moments of their route. To that effect, the artist’s orientations intend to encourage participants to take part in an apparently lonely action, but, in fact, Steindorf is constantly present through her voice and ambient noises that accompany her propositions, as if she herself were executing them simultaneously. “I’ll wait for you to get ready so that we can go for a walk,” suggests the artist in the beginning of the audio walk, followed by the sound of footsteps, jingling keys and a door closing. Adding to this allusion to Steindorf’s presence, the scheduling of a common time allowed for a synchronised participation in the audio walk, as if these women were in fact walking together, despite the geographic distances between them.

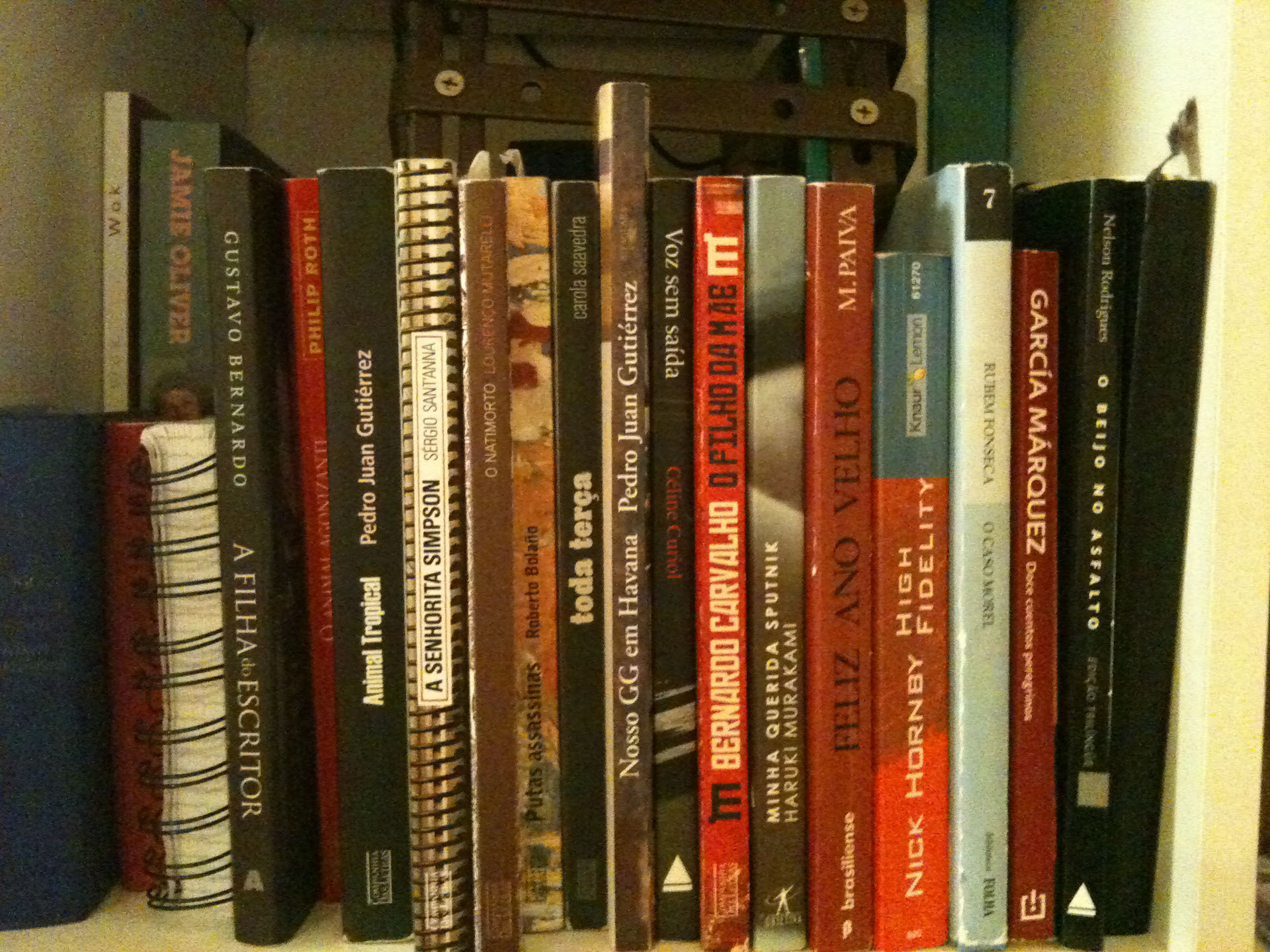

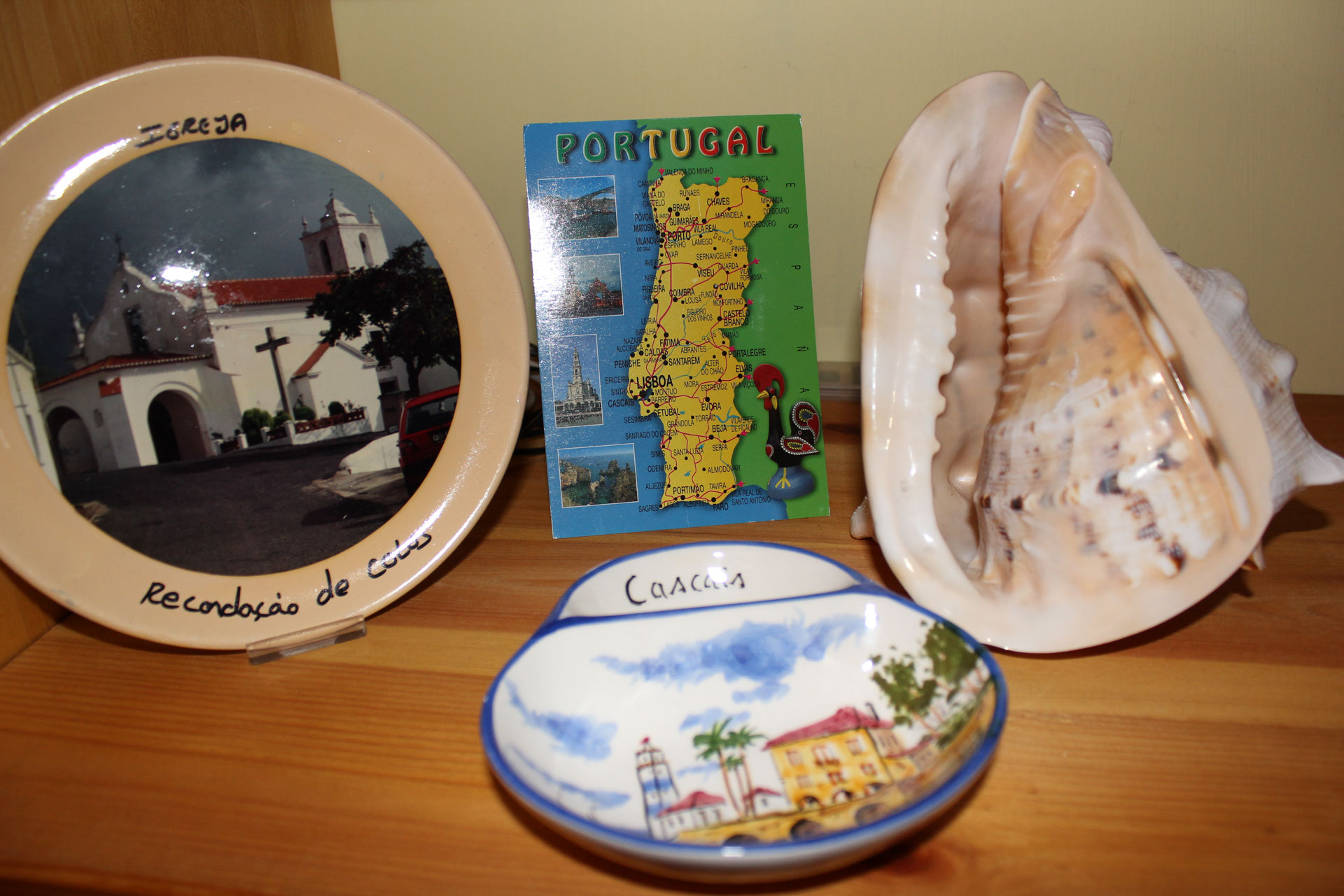

Other narratives crafted by the artist are used to complexify, from the beginning, the structure of the piece. The instructions, given in English, are intertwined with soundbites, in German and Portuguese, evoking memories of the artist’s childhood, teenage years and adult life - spanning across Brazil, Portugal, Mexico and Germany - and raising questions about her own condition as an immigrant. In this context, by associating the tangible daily presence of home - the house, the neighbourhood - to a broader, more open and fragmented idea of home emerging from the artist’s reflection about her own idea of transnational circulation, the audio walk stimulates an exploration of the relationships between multiple layers of meaning present in home as a theoretical, material, affective and imaginary construction. As geographers Alison Blunt and Robyn Dowling put it, “Home […] is a place, a site in which we live. But, more than this, home is also an idea and an imaginary that is imbued with feelings. These may be feelings of belonging, desire and intimacy (as, for instance, in the phrase ‘feeling at home’), but can also be feelings of fear, violence and alienation […]. These feelings, ideas and imaginaries are intrinsically spatial. Home is thus a spatial imaginary: a set of intersecting and variable ideas and feelings, which are related to context, and which construct places, extend across spaces and scales, and connect places.”⁽⁴⁾

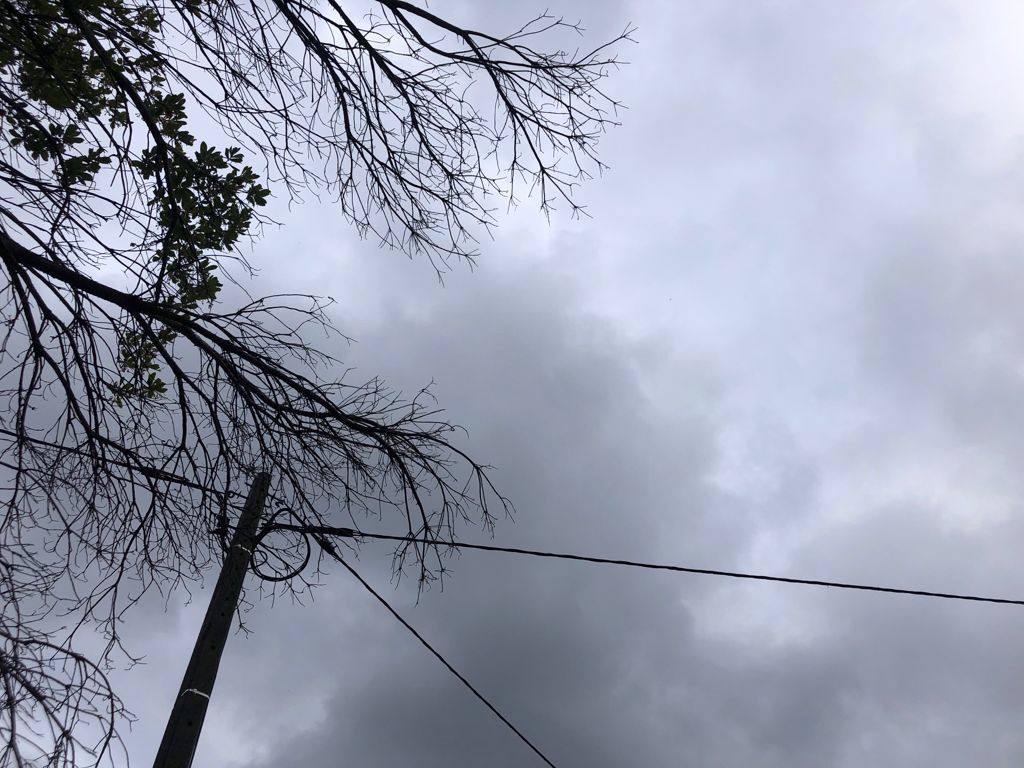

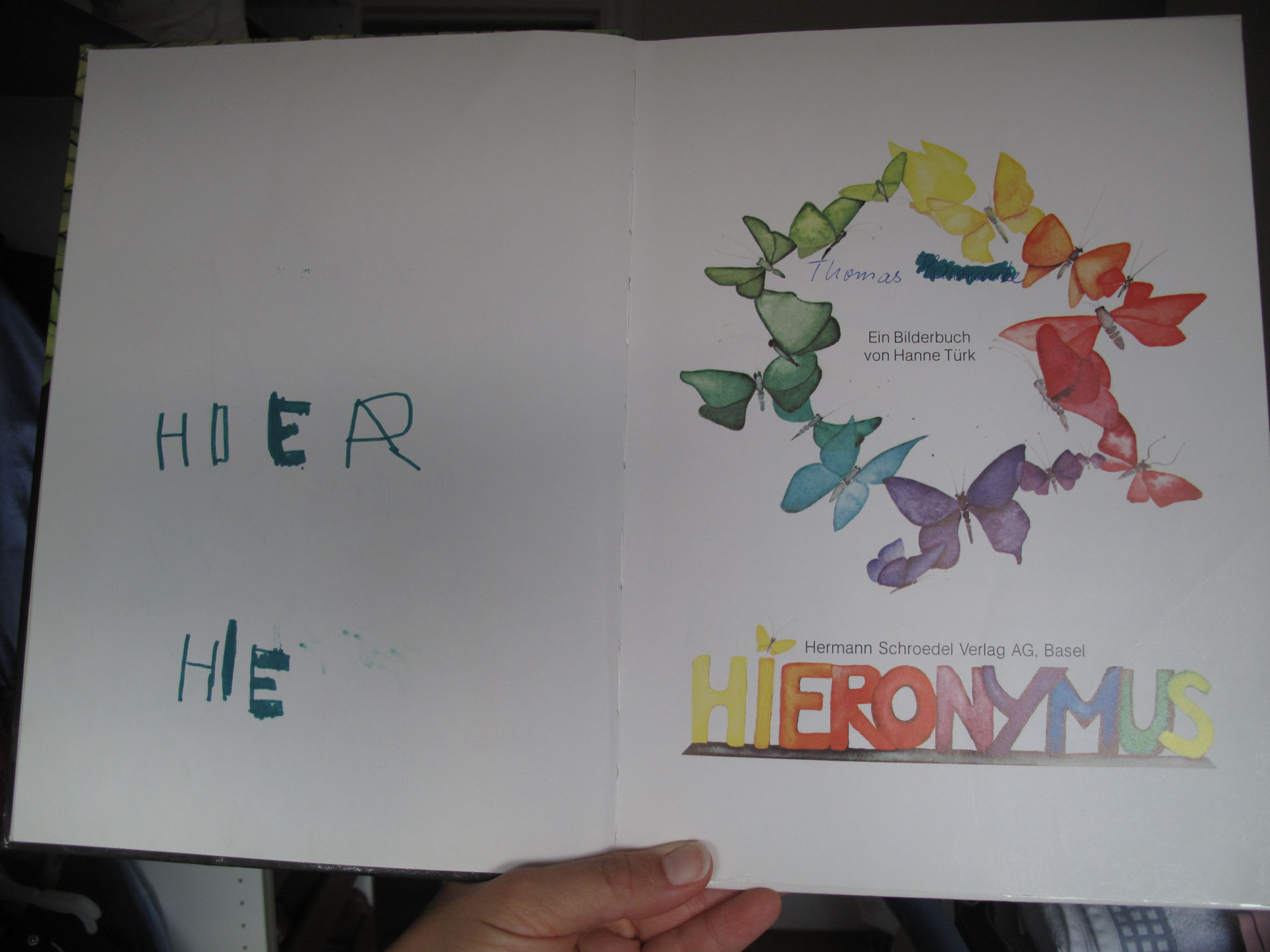

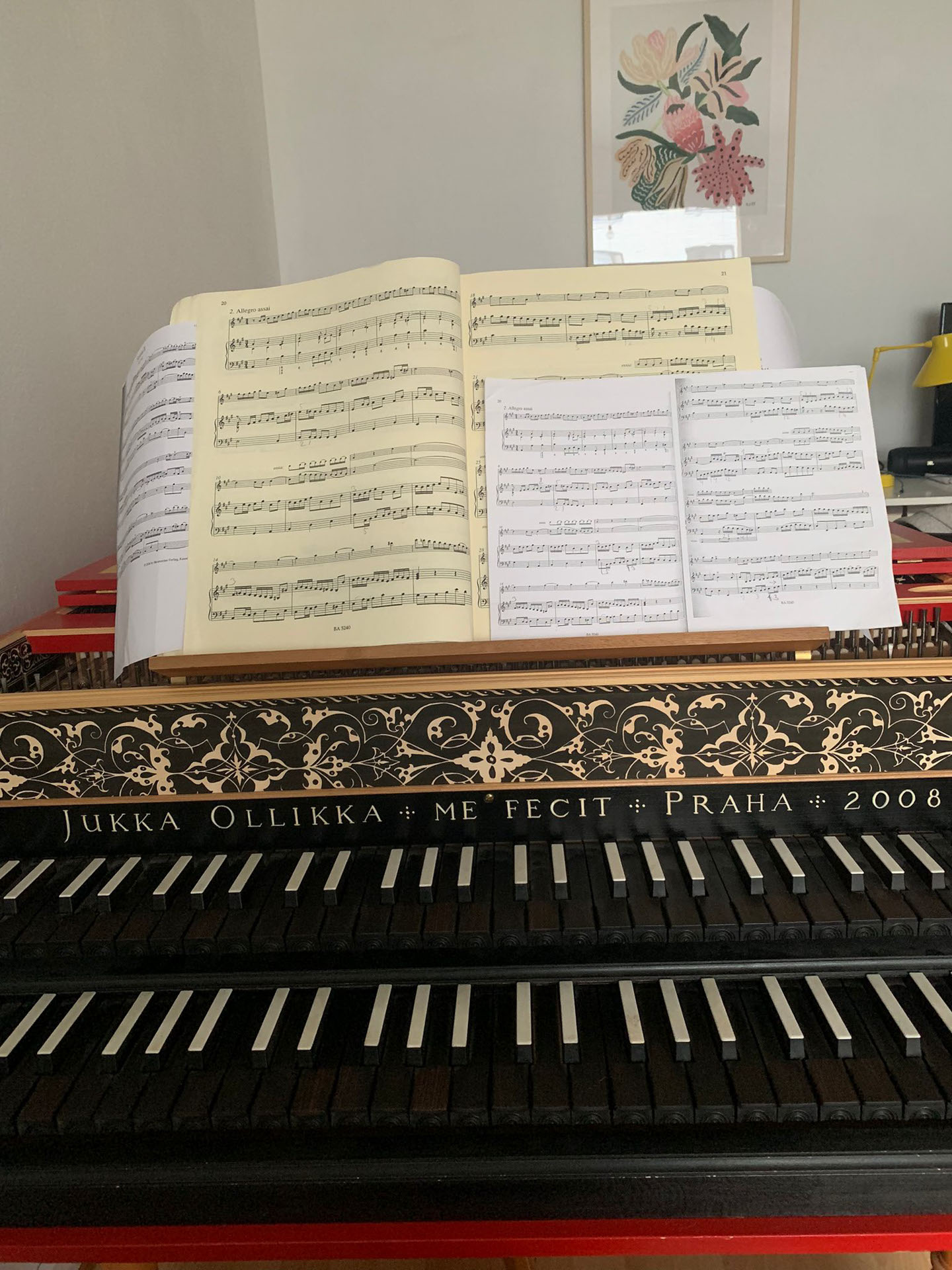

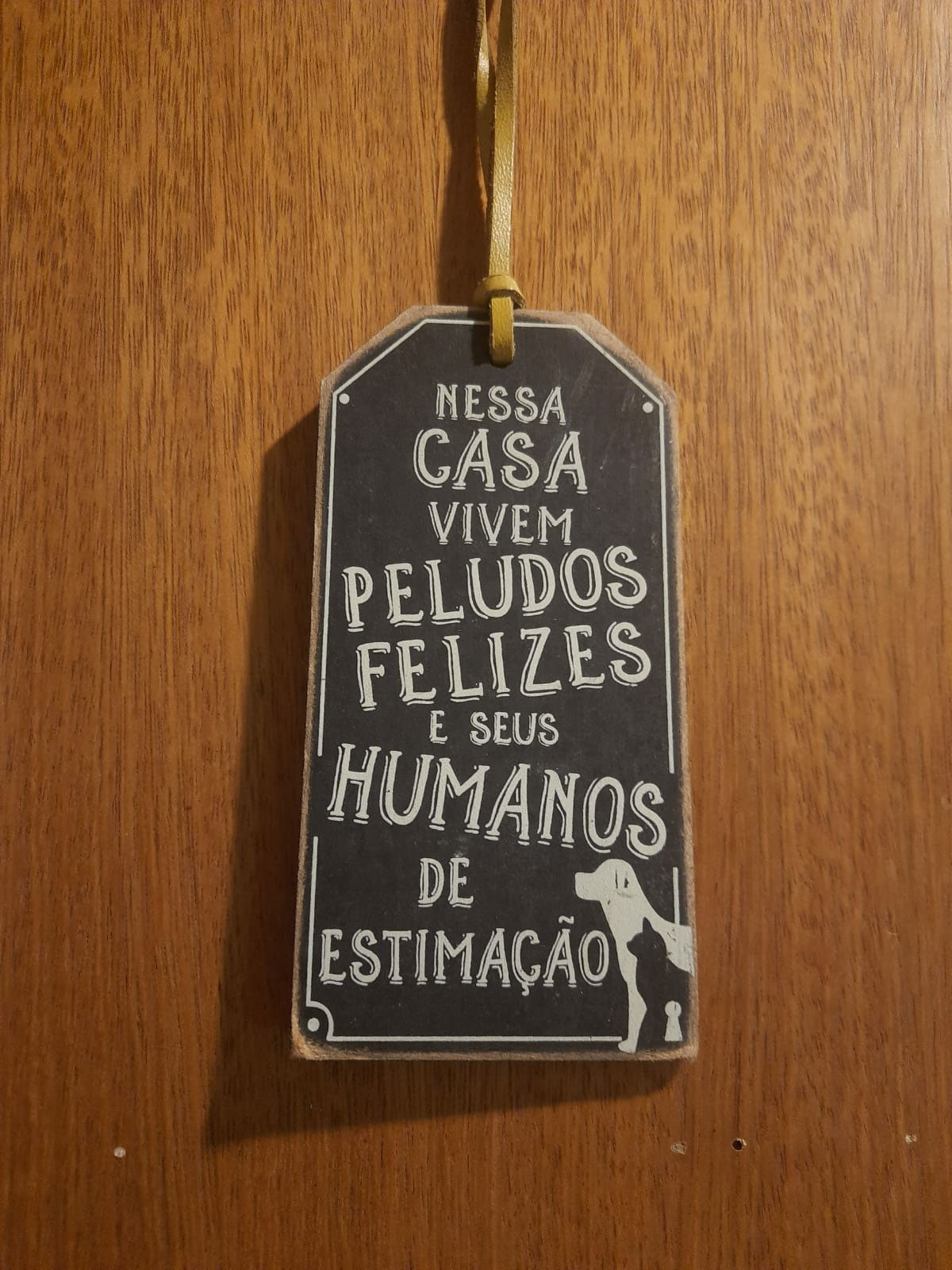

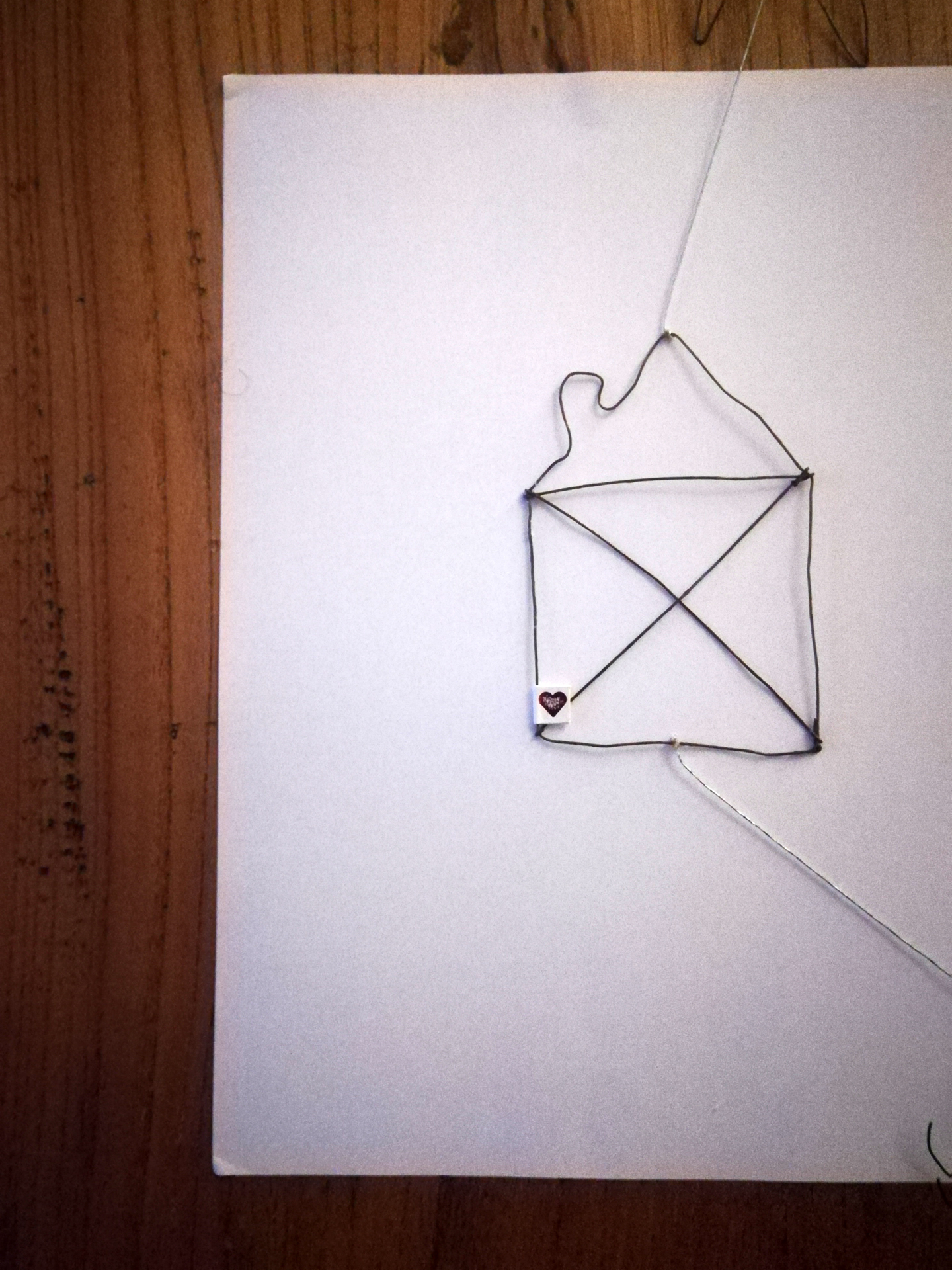

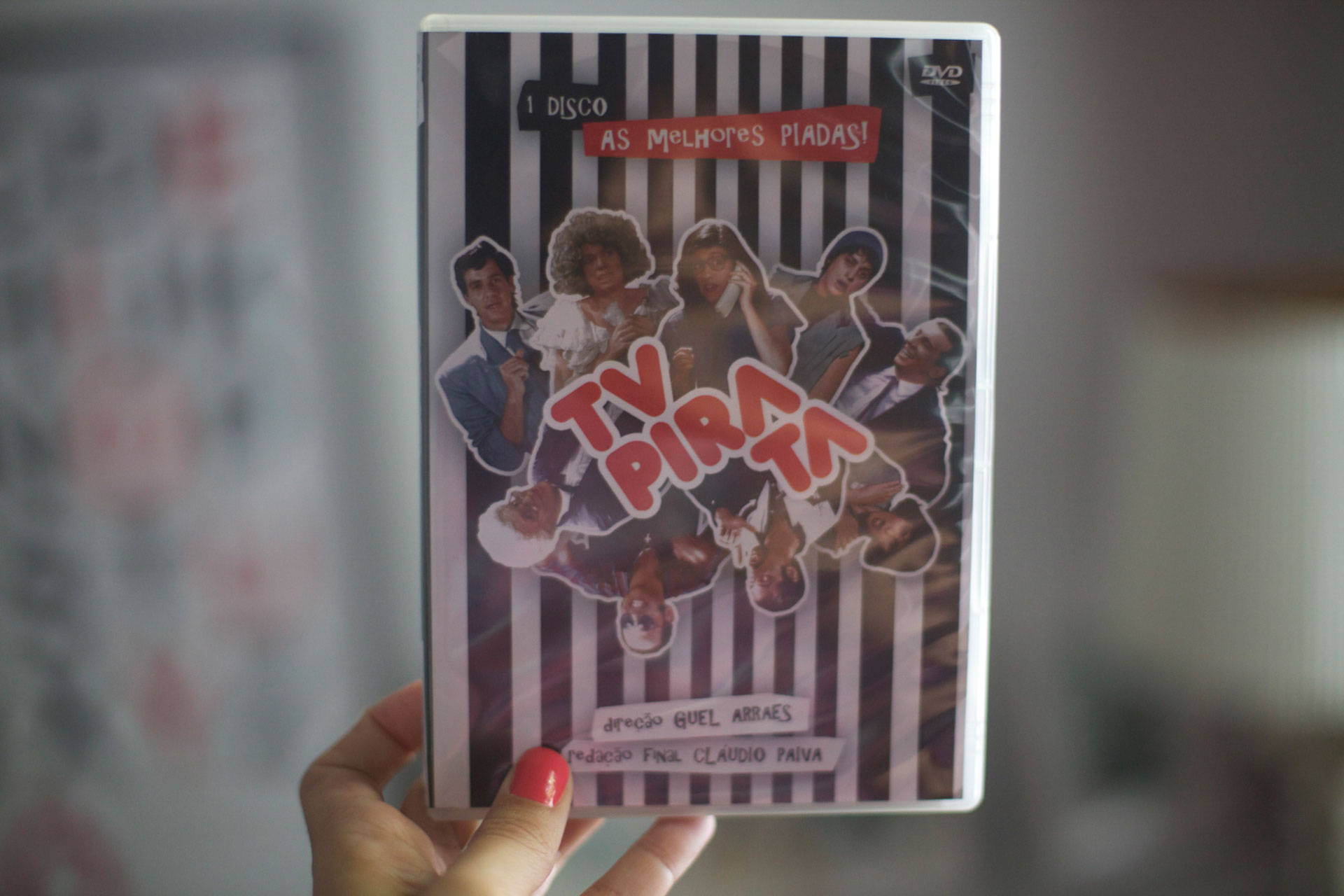

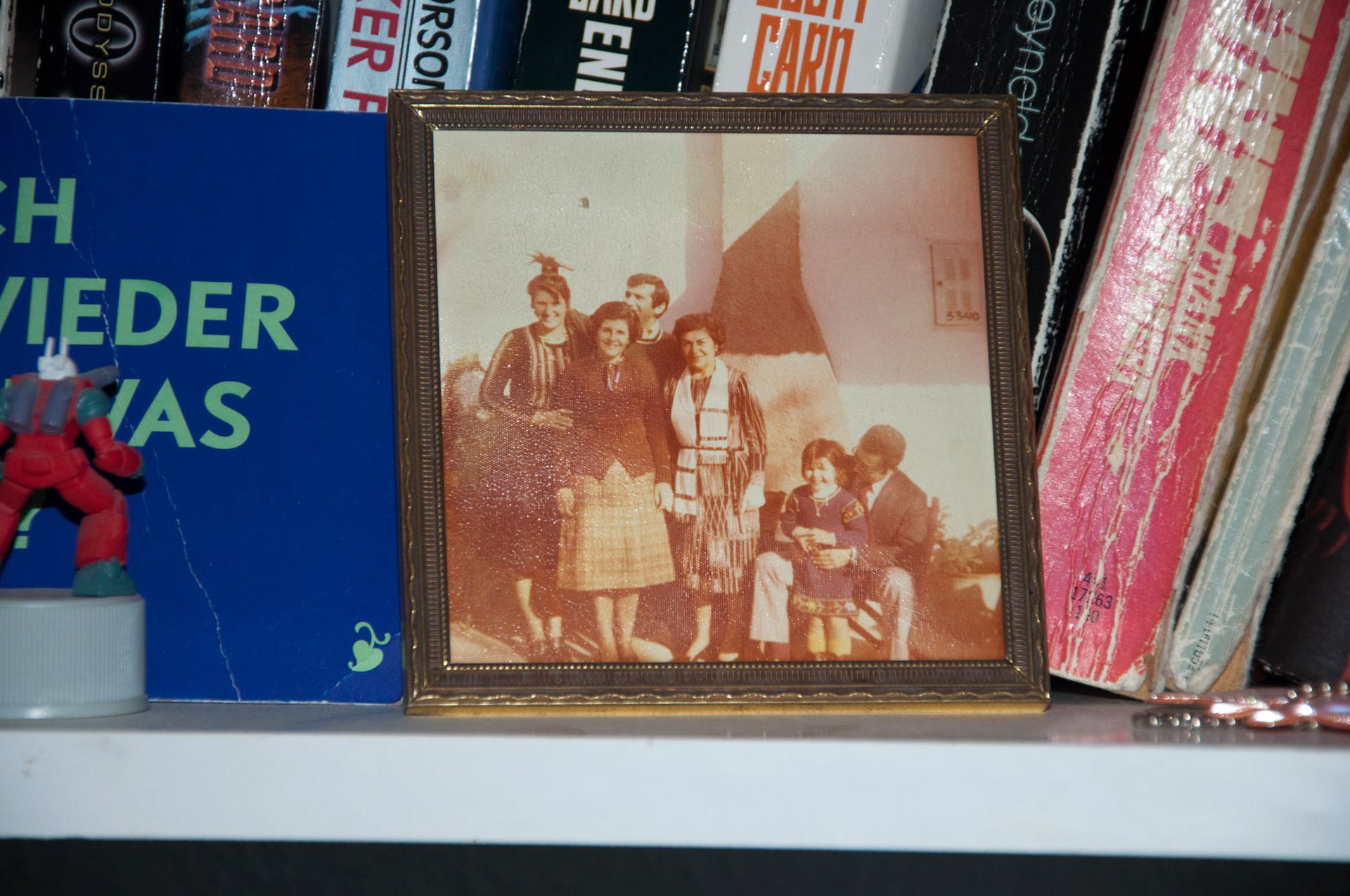

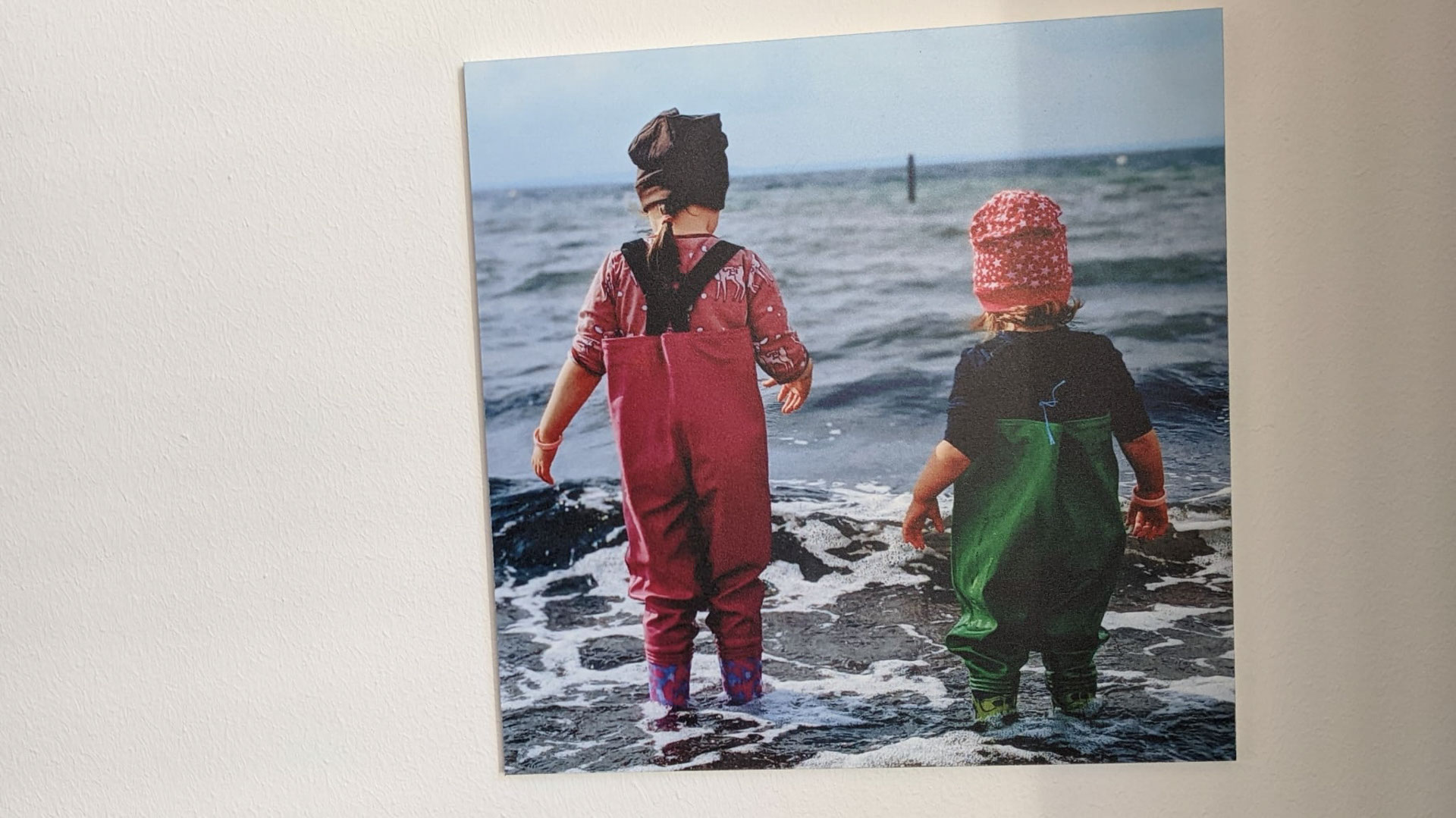

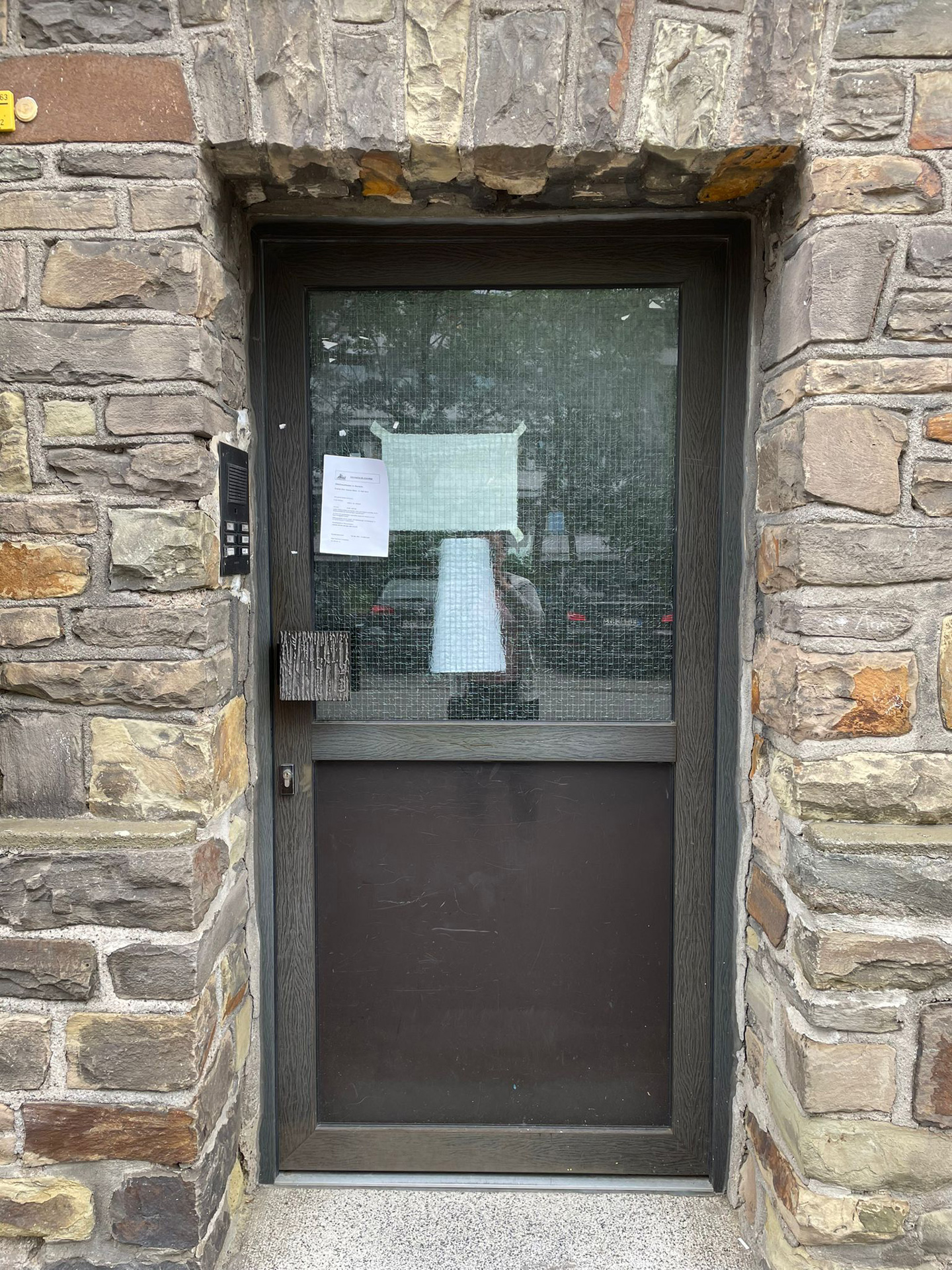

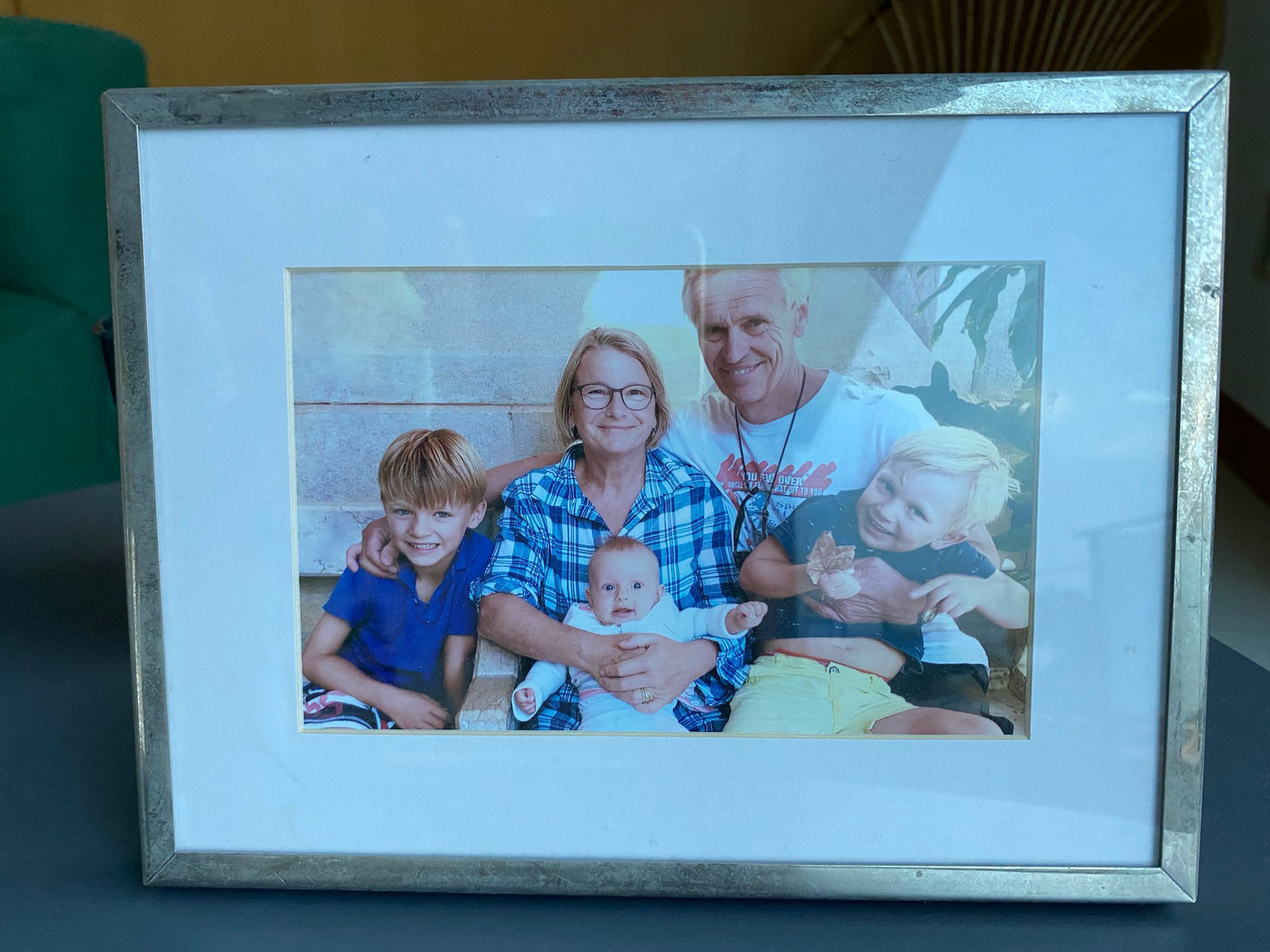

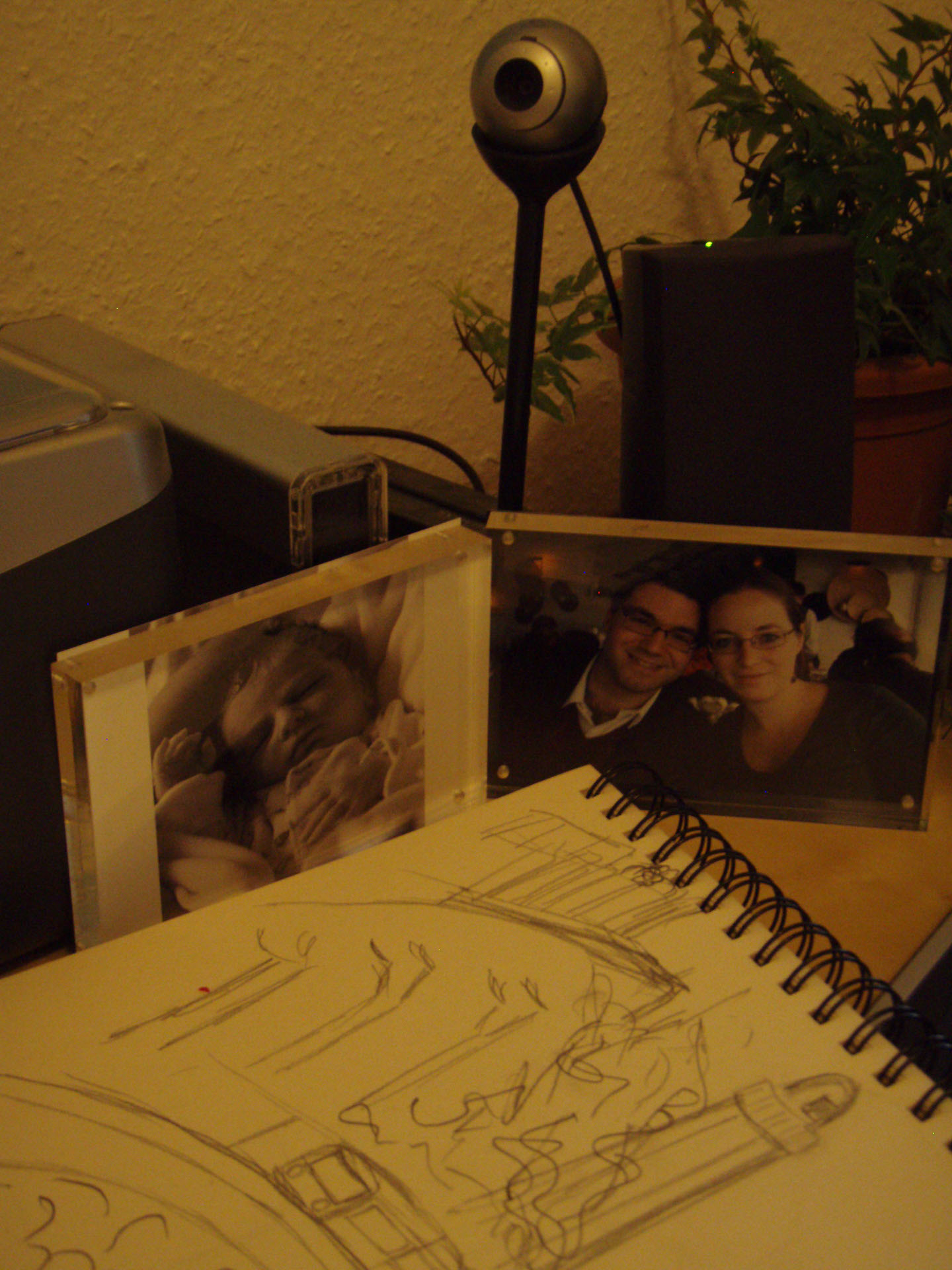

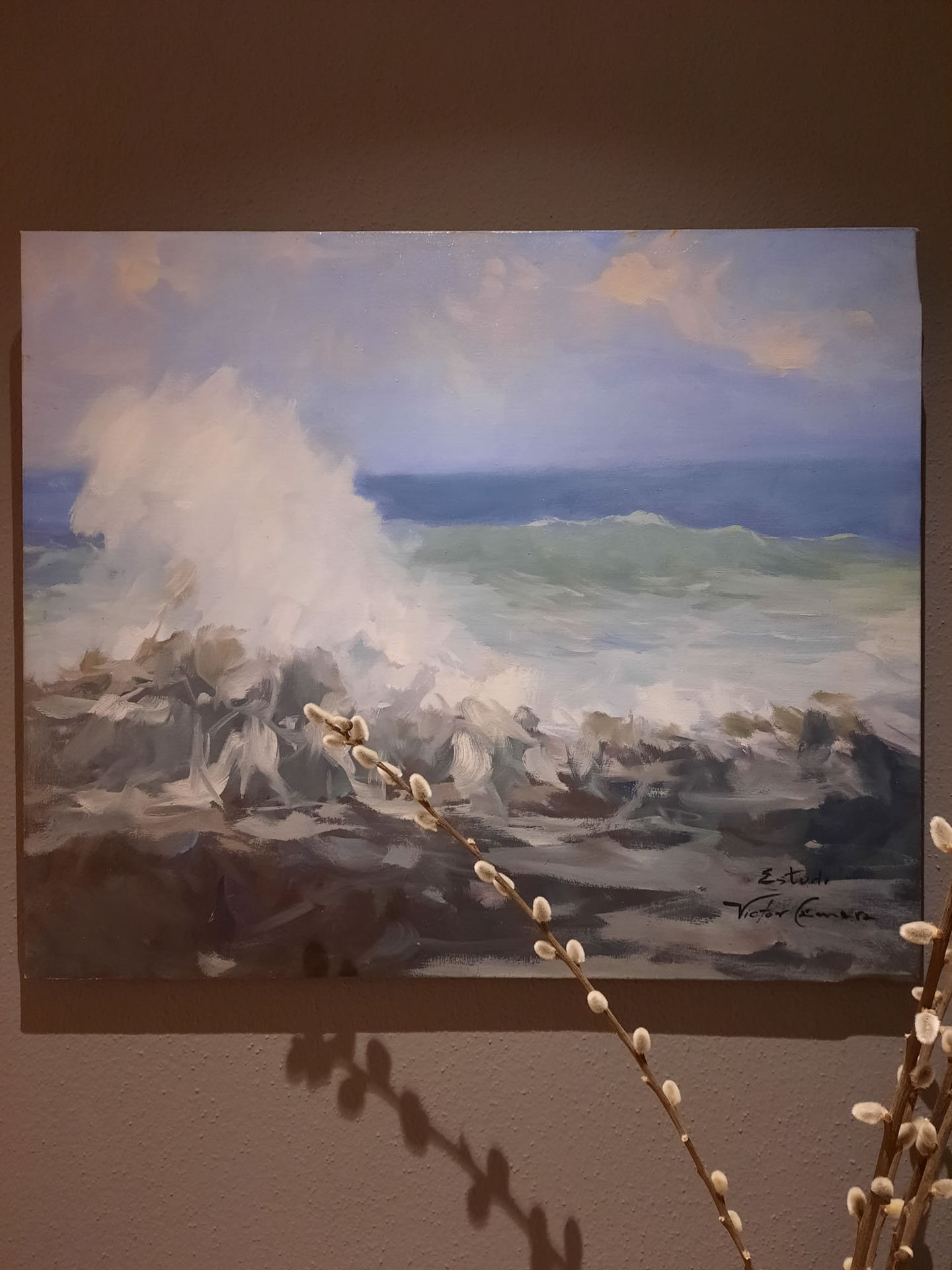

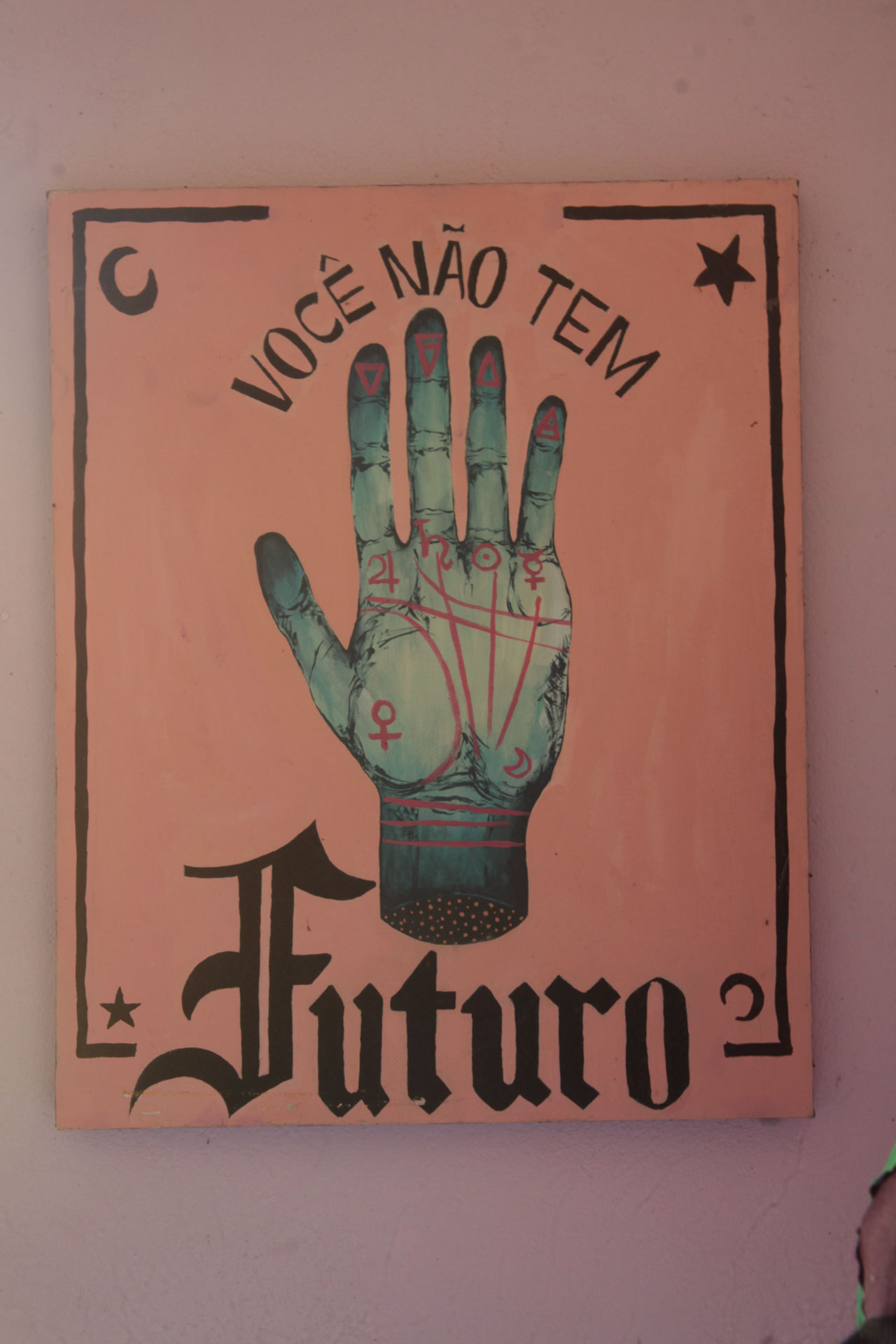

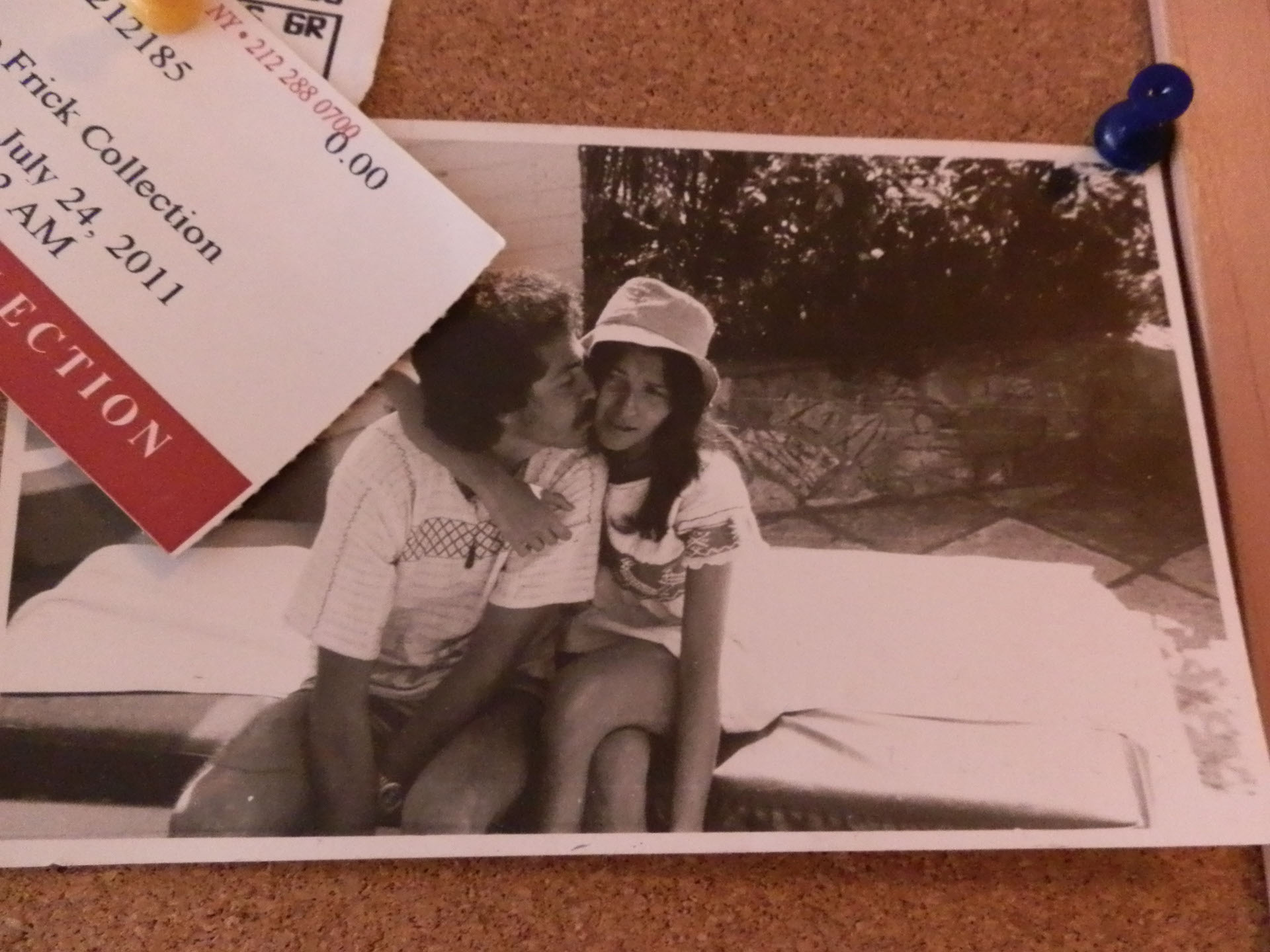

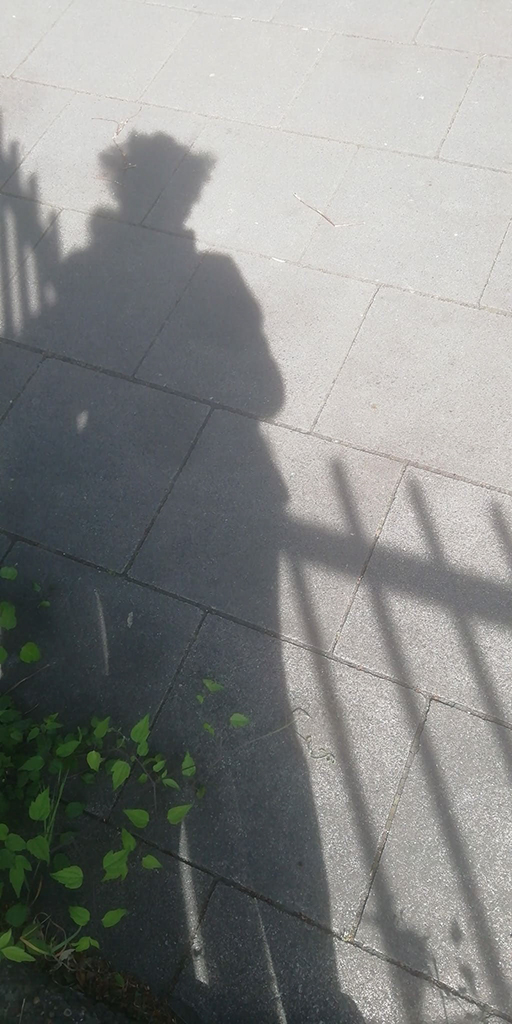

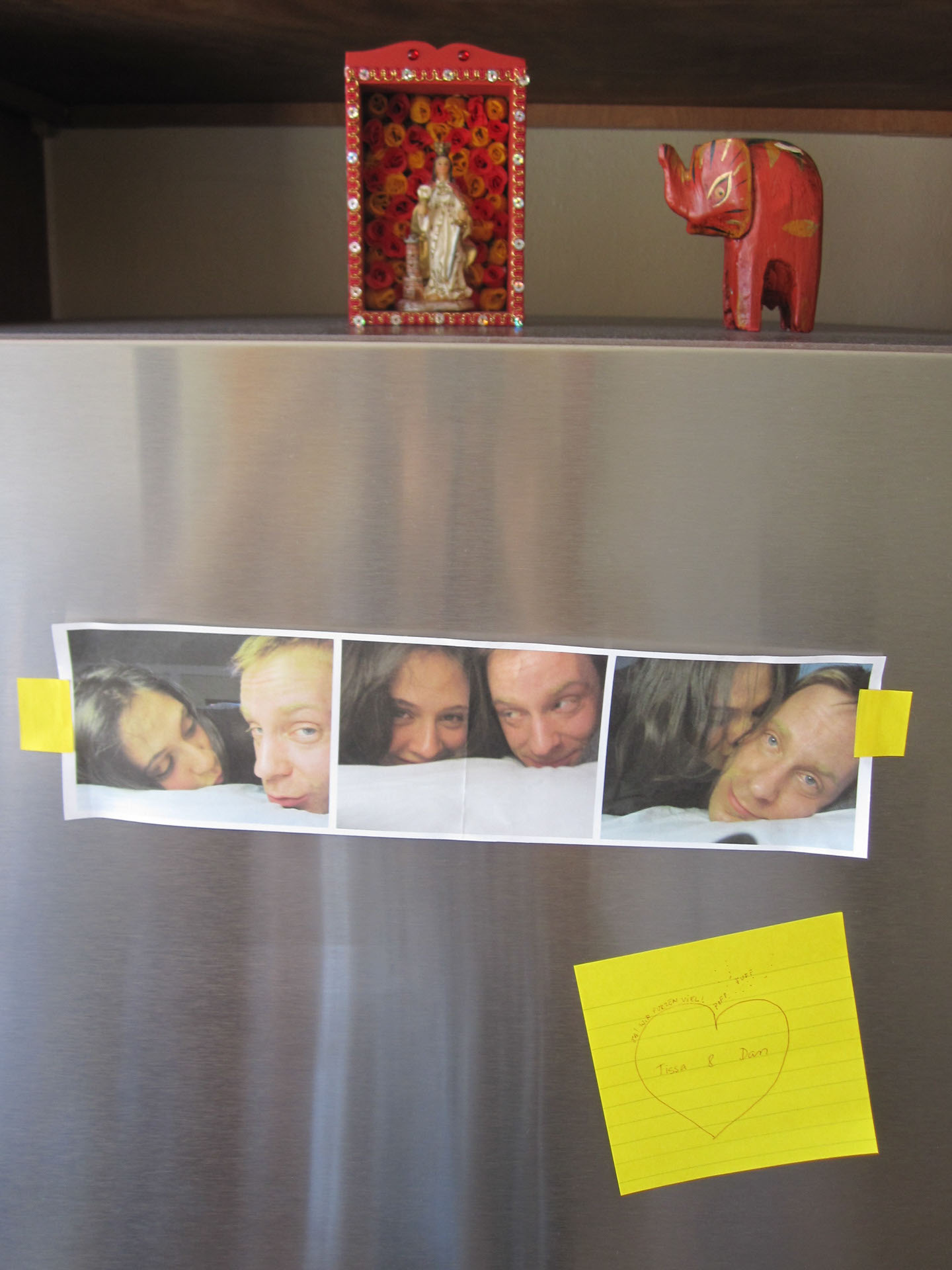

If the notion of home mobilises multiple scales of belonging - from a dwelling, to family, to nationality and other forms of social and spatial enrollment - its capacity to signify affective and symbolic connections generated in the space between different places, languages and forms of cultural expression is particularly relevant in transnational migration processes such as the ones mobilised by the narratives present in Steindorf’s audio walk. But what happens, and how does one live, day after day, when the affective and imaginary home is situated in between? Johanna Steindorf’s audio walk, activated by women who, like her, migrated due to personal choice - “I decided to leave when, for the first time, I didn’t have to go” she says - suggests that, at times, home is constructed both through the material presence of a house, objects and daily rituals, as well as the spectres of that which is absent. And so, in this piece, the artist asks participants to photograph, in sequence, their front door, the sky above, the ground below, themselves, something representing home and, finally, something that reminds them of what they miss the most. Memory, thus crystalized in those pictures as well as in the artist’s words, becomes an instrument capable of mending, at least temporarily, presence and absence in a single sensitive space.

Ten years later, in 2021, some of the audiowalk participants take the camera in their hands once again and repeat the experience, but now, for the first time, when interviewed by Steindorf, they also take the floor. Memory is once again a central element in the process instigated by the artist. To that effect, in their oral testimonies, the interviewees try to remember, more or less successfully, of their participation in the 2011 piece. This work of remembrance brings forth diverse reflections upon the practical as well as symbolic transformations that have occurred in their lives over the past ten years, with a particular focus on how their views on home and their experience of public space has changed over time. So the questioning of the mutable character of the imaginary and affective construction of home juxtaposes, in some of the testimonies, the difficulty of being a foreigner, the realisation of being torn. “It’s very hard being a foreigner”, says Ilana, for example, while Louise considers that “...one becomes divided. You end up with no identity or with a very complex and multifaceted identity. For some participants, on the other hand the idea of home ends up coinciding with their own self, their own identity: “I am my home” says Joana, and Fernanda states that “today more than ever, for me the sense of Heimat is inside''. For others, the sense of home as a place of origin is lost - “we never feel totally at home, you know, after the experience of a few years living in another country. I think I’ll never have the feeling of home like I used to” says Ilana.

In one of the most challenging testimonies, Nerita refuses to approach the processes of migrating or staying put as opposites, pointing out the risk of a certain romanticising of this movement. “I used to value migration.” says Nerita, “ and today I think I really value those who could stay, who chose to stay in the same neighbourhood, in the same house, in the same city, in the same country. I think I used to glamourize migration a little bit. But nowadays I think it’s just one of the many ways of experiencing the world, and they’re all valid.” These words are a reminder of the need to go beyond the limitations of a binary approach, to “[…] challenge the presumptions that movement involves freedom from grounds, or that grounded homes are not sites of change, relocation or uprooting. Being grounded is not necessarily about being fixed; being mobile is not necessarily about being detached”⁽⁵⁾ and “[…] to call into question the naturalisation of homes as origins, and the romanticization of mobility as travel, transcendence and transformation.”⁽⁶⁾

The plurality of testimonies gathered and activated by Johanna Steindorf in this project makes reference, to an effect, to the impossibility of narrowing down the diversity of conceptions of belonging - in the context of migration - to a single pattern. On the contrary, what these statements seem to do is open up an intersection between a focus on home as an imaginary and affective configuration, mutable through time, and a focus on the daily process of construction and deconstruction of home. This labour, which involves the act of caring in a crucial way, can become more complex, or even impossible, due to geographic distance. Joana, for example, says: “The fact that I’m far away while my parents are getting older came to me as a regret, really, for not thinking this decision all the way through. And the meaning of migration changed a lot after having children of my own. Before, I wasn’t fully aware, because I could return to Brazil at any given moment and now I can’t anymore. So the idea of migration gets more complicated, my feelings about it, and it often comes along with a feeling of regret, yes.”

But at the same time as it discloses the difficulties related to the lag between affective closeness and spatial distance, Johanna Steindorf’s work tests immaterial possibilities of generating intellectual and emotive connections - creating, above all, a community of listeners, participants and companions through physical and reflective paths. As a means to an end, digital instruments are used by the artist - the web allows for contact and exchange with participants, the transmission of photos taken by mobile devices, the recording of statements and, finally, the development of a map and website which allow the public to access the project. But maybe a more relevant instrument in this context is voice - the recording of the artist’s voice and those of the women participating in the project’s unfolding in 2021. To an effect, the voice materialises the singular presence of the body through its “grain” – “The 'grain' is that: ” writes Roland Barthes, “the materiality of the body speaking its mother tongue”⁽⁷⁾. Through her voice, recorded in the audio walk, the artist accompanies the participant’s trajectories through their everyday places. “And it’s funny because I felt like you were there with me the whole time,” says Camila, “and we were strolling together.” Inversely, the participants' voices, available for listening through the project’s website, materialises their incarnate singularities bringing forth, to the general audience, the community developed through and around the artwork.

Finally, the mobilisation of speech in Johanna Steindorf’s work points out the existing connection between the embodiment and experience of space, at the same time evidencing that the building of a home is always a relational process. Says Ilana: “The sense of body, for me, was fundamental in my decision to return, to not be a foreigner anymore.” But what does it mean to be a foreigner? Clarice Lispector’s short story reminds us that it’s not necessarily leaving that turns one into a foreigner. An unpredictable detail somewhere extremely familiar may be more than enough to set off a storm which, instantly, knocks down a house that seemed quite solid. In that way, the blind man chewing gum may represent, for Ana, the repetitive gestures and the isolation necessary in the daily construction of her home and give her that sense of rooting which brings about satisfaction and tranquillity. But from one moment to the next, the eyes may open up to the world and to desire, and that same house might come undone through other gestures, other ideas, other imaginaries.

¹Clarice Lispector, Laços de família, Lisboa, Relógio de Água, 1990, p.18.

²Ibidem, p.17.

³Some of the women who took part in the 2011 audio walk accepted the artist's invitation to repeat the experience in 2021.

⁴Alison Blunt, Robyn Dowling, Home, London and New York, Routledge, p. 2.

⁵Sara Ahmed, Claudia Castañeda, Anne-Marie Fortier, Mimi Sheller, “Introduction”, in Uprootings/Regroundings. Questions of Home and Migration, Oxford, New York, Berg, 2003, 1.

⁶Ibidem.

⁷Roland Barthes, “The grain of the voice”, in Image Music Text. Essays selected and translated by Stephen Heath, London, Fontana Press, 1977, p.182.